Frank Gehry's bold plan to upgrade the L.A. River seeks to atone for past injustices

Note by John Kosta: After years of documenting the undiscovered beauty that lay in the once abandoned Los Angeles River, it is wonderful that awareness of this important waterway is gaining well deserved attention. Gehry's unique creative perspective and commitment to themes of social justice is a welcomed addition to the work being done.

Although Gehry’s participation is helpful in bringing awareness to the revitalization project, it will be useful to consider, as the project develops, how the participation of a world-renown architect may impact issues of affordability for residents in the area — a key cornerstone of the dialogue taking place with the Los Angeles River Revitalization Project.

The

Los Angeles River Series

art project is a large-scale multi-year initiative by California fine artist John Kosta. The series documents the artist's impressions about the river in an effort to call attention to its beauty as it is, as well as what might be, as envisioned by the Los Angeles River Revitalization Project. To learn more about the series and the revitalization project, see below.

In the decades since engineers first blanketed the Los Angeles River with concrete, working-class communities along its armored banks have struggled with blight, poverty and crowding — unintended consequences perhaps of an epic bid to control Mother Nature.

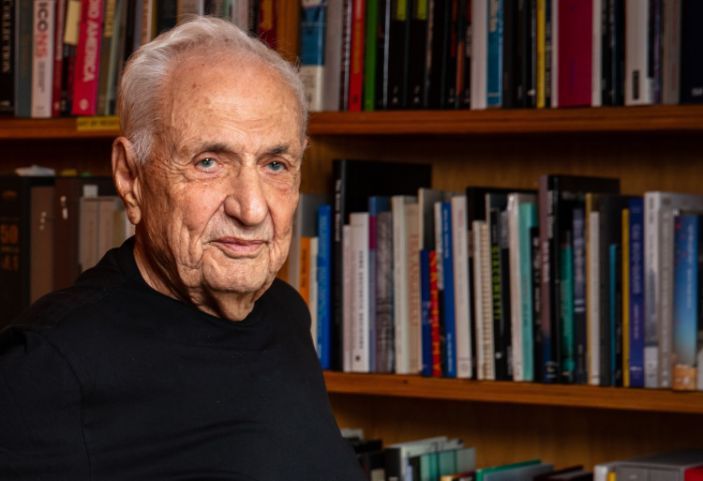

Now, as many of these neighborhoods suffer disproportionately higher rates of infection from COVID-19 — and as the nation seeks to atone for racial and institutional injustices laid bare in the police killing of George Floyd — famed architect Frank Gehry has unveiled a bold plan to transform the river into more than just a concrete flood channel and establish it as an unprecedented system of open space.

For more than half a century, Gehry has been better known for sketching ideas that became flashy cultural and commercial landmarks, such as the dazzling Walt Disney Concert Hall, whose tilting forms have reinforced Los Angeles' place among the world’s great urban centers.

Today, the 91-year-old has emerged as a lead architect in far-reaching proposals designed to uplift the profiles of Southern California’s poorest, most densely crowded communities along the backbone of the county's flood-control system.

Critics, including some influential environmental groups, would prefer to see naturalization of the river itself. But during a recent Zoom call from his Los Angeles studio, a grin crossed the Pritzker Prize winner’s face as he shared his plans to transform the forlorn industrial confluence of the Los Angeles River and the Rio Hondo in South Gate into an urban cultural park like no other.

“We studied the river upside and down and found that less than 2% of the time it runs very fast and is very dangerous,” he said. “So, we thought if we can’t get rid of the concrete, maybe we can cover it.”

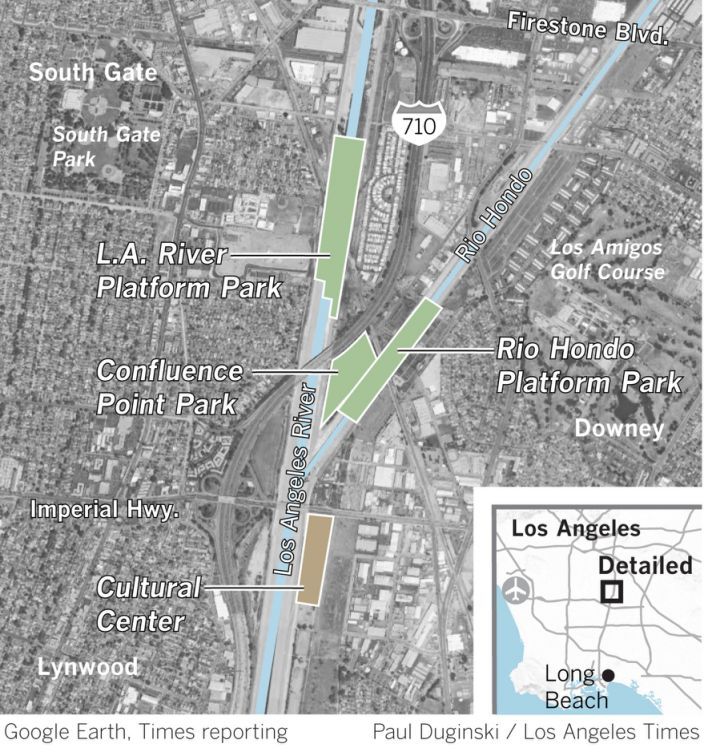

Picture “elevated platform parks” — massive, bridge-like green spaces that occupy government airspace high above the flood channel's musty floor, and four feet above the rim of the channel walls. Constructed on hulking concrete planks and enormous girders, the earthen parks would stretch nearly a mile over both rivers and support a lush landscape of trees, grass, scenic ponds, horse trails and walking paths.

Nearby, children from throughout the region would mill around the courtyard of a $150-million cultural center, taking lunch and sharing what they learned there about music, dance, painting, culinary arts, ceramics, photography and filmmaking.

The platform parks are big-ticket projects that could take a decade or more to build. But the cultural center, which has the support of influential state, county and local lawmakers — and would be just a stone’s throw from a proposed Metro transit hub — could be realized much sooner.

“I’m excited about the cultural center and want to see it built,” Gehry said. “I think it will grow into something very special because it is so important to future generations. The life expectancy of kids south of downtown is 10 years shorter than it is elsewhere.”

His ideas arose from research and meetings with community leaders in such riverfront towns as South Gate, Downey, Maywood and Paramount — communities where a dearth of open space and other urban woes long ago tarnished their ZIP Codes.

It may sound like an idealist’s dream, but it builds on potential improvements and water management policies floated in Los Angeles County Public Works’ new 2020 master plan for the Los Angeles River along its entirety, from Chatsworth to Long Beach.

The updated document’s recommendations for the next 25 years take their cues from increased occurrences of extreme weather events due to climate change. But another goal is a reckoning with a legacy of flood control that “subjected riverfront neighborhoods to overt discrimination along racial and ethnic lines.”

Areas off the river’s east bank near downtown L.A., for example, were described by home lenders as being honeycombed with "diverse and subversive racial elements,” according to the river master plan.

“This classification established major barriers for residents seeking home loans and stalled their upward economic mobility,” it says. “Neighborhoods bypassed by this grading exercise tended to have more affluent and homogenous populations and were, by contrast, set up as white suburbs.”

Redlining, it says, produced landscapes of segregation that both created and reinforced racial and ethnic enclaves along the river: Chinatown, Bronzeville and Sonoratown. The legacy endures, it says, "particularly in the San Fernando Valley and south of downtown, where some Latino and Asian communities today are disproportionately challenged by deteriorating social, economic and environmental conditions.”

More recently, construction of the freeway system during the 1950s and ’60s displaced nearly 250,000 people. Today, the 710 Freeway, which runs adjacent to the lower L.A. River, contributes to the poor air quality and heightened disease rates of nearby neighborhoods.

“Revitalizing the river south of downtown offers our southeast communities an opportunity to rebuild our connections, to the river and each other,” said Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood), whose 63rd Assembly District includes South Gate, Bell and Long Beach.

“Southeast L.A. deserves parks and trails, education and cultural centers,” he added. “Equity comes when every community has access to the tools to make life better.”

The partners in Gehry's firm who have been overseeing research on the river and preliminary project designs — alongside prominent landscape architect Laurie Olin, whose projects include the Getty Center in Los Angeles, and Mark Hanna, a water resources engineer at Geosyntec Consultants — say they aren't ready to unveil any formal proposals.

Whether their plans become reality hinges on their ability to compromise.

The river master plan has no legal jurisdiction over land use, and no authority to implement its recommendations. Ultimate decisions about what happens along the lower river corridor will be made by the county and the 14 cities that border it, many of them impoverished, working-class enclaves where local politics is often a clamor of conflict and scandal.

Still, Carolina Hernandez, principal engineer for countypublic works, is optimistic. “I can see the platform parks happening within 10 years,” she said. “But it will depend on local decisions and availability of funding because they will cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

”Denise Diaz, 34, a South Gate city councilwoman and lifelong resident of the area, hopes to see the cultural center open in 2024. “A significant project like this,” she said, “could help transform our long-overlooked landscape into a prime location shared by thriving, walkable and healthy communities.”

Paul Adams, South Gate parks director, however, urged patience. “It is exciting to see the lower river communities finally getting the attention they deserve,” he said. “But at this early phase of the process, everyone needs to take a few grains of salt along with it.

“Even projects designed by architects of this stature tend to shrink fast,” he added, “in the face of the cold-hearted reality of political and budget considerations.

”Whether the area in the vicinity of the confluence can survive as it is today — a gateway for new arrivals and a sea of low-rise industrial and commercial districts where 72% of all businesses are minority owned — is an open question in the minds of some community leaders. They fear that Gehry’s high-profile amenities will attract upscale developers, leading to displacement of thousands of people who now call it home.

Housing affordability is a key goal of the river master plan embraced by L.A. County Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district includes struggling communities in the southeastern part of the county. For decades, these areas have been plagued by environmental affronts, including insensitive land use and pollution from freeways, railyards and industrial sites laden with toxic substances.

“The gatekeepers of these proposals will be the people who live among them,” she said. “We must make sure that they are culturally sensitive to the area, set aside land for senior citizens and keep housing stock affordable.

There are signs that gentrification is already underway. In Maywood, which with 30,000 residents crowded into 1.13 square miles is the most densely populated city in California, typical home values surged about 10% over the last year to roughly $482,000, according to Zillow Real Estate Research. Zillow predicts they will rise more than 10% in the next year.

Community-based nonprofits, whose revenues shrank but whose expenses remained during the COVID-19 pandemic, are asking stakeholders to step up their support.

“Nonprofits play a huge role in sewing the fabric of a community,” said Miguel Luna, who serves on both the Statewide Watershed Partnership Program and the city of L.A.’s Pedestrian Advisory Committee. “We have to ensure that they have the ability to continue to do so in a robust and fair way — as opposed to cities and developers.

”Taking a less welcoming position, some environmentalists say that installing platform parks is about the worst thing you can do to the river and adjacent communities. Ever since Gehry listed them among the ambitious projects he wants to design in the autumn of his career, anger and fear have simmered.

A coalition of environmental groups led by Friends of the Los Angeles River, Heal the Bay, the Nature Conservancy, Los Angeles Waterkeeper, the Trust for Public Land and East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice threatened in November to withhold support for the river master plan if any mention of such structures was not removed before its publication.

“This proposal stands to do particular ecological harm,” the group argued in a letter to county officials, “create real estate speculation, and precludes future opportunities for climate resilience."

“More concrete,” it added, “does not help any of these issues or support the goals and methods described in the plan.” (...)

This article originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times on Monday, January 11, 2021 (Louis Sahagún).

View the complete original article.

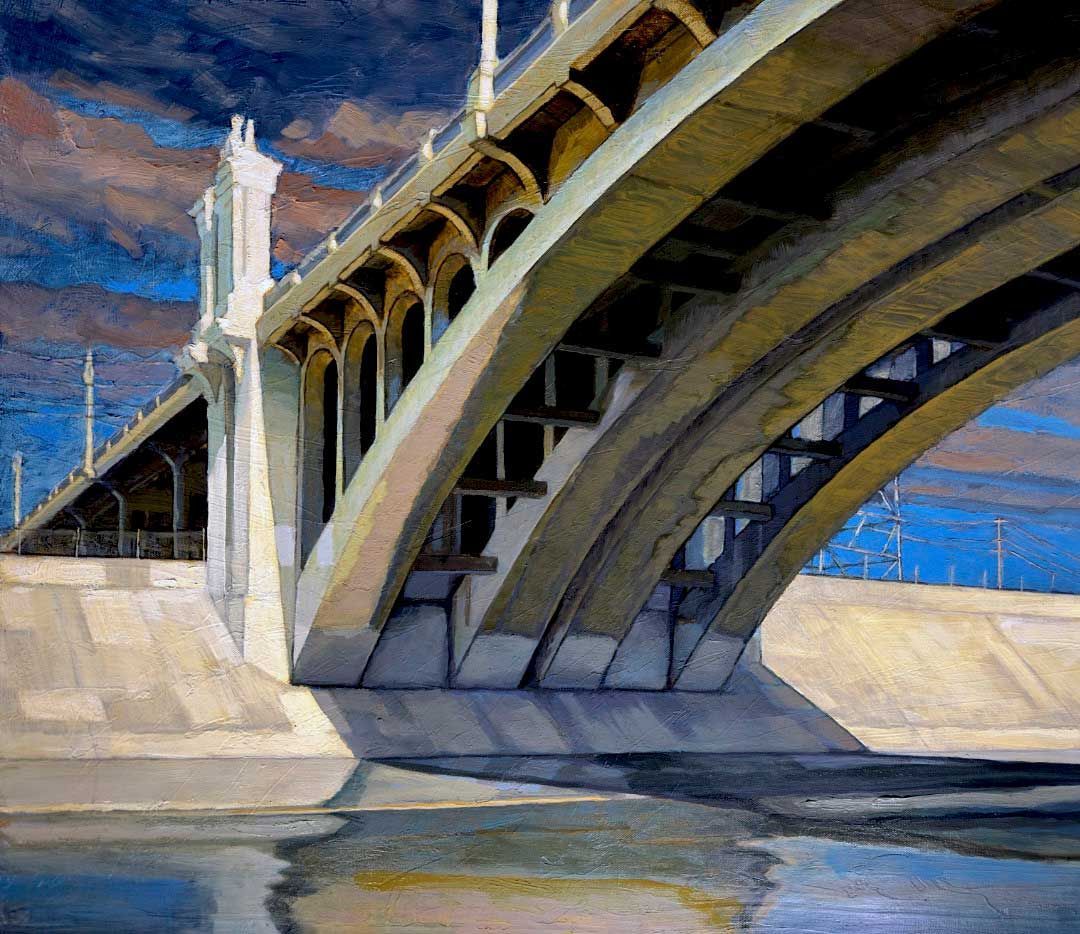

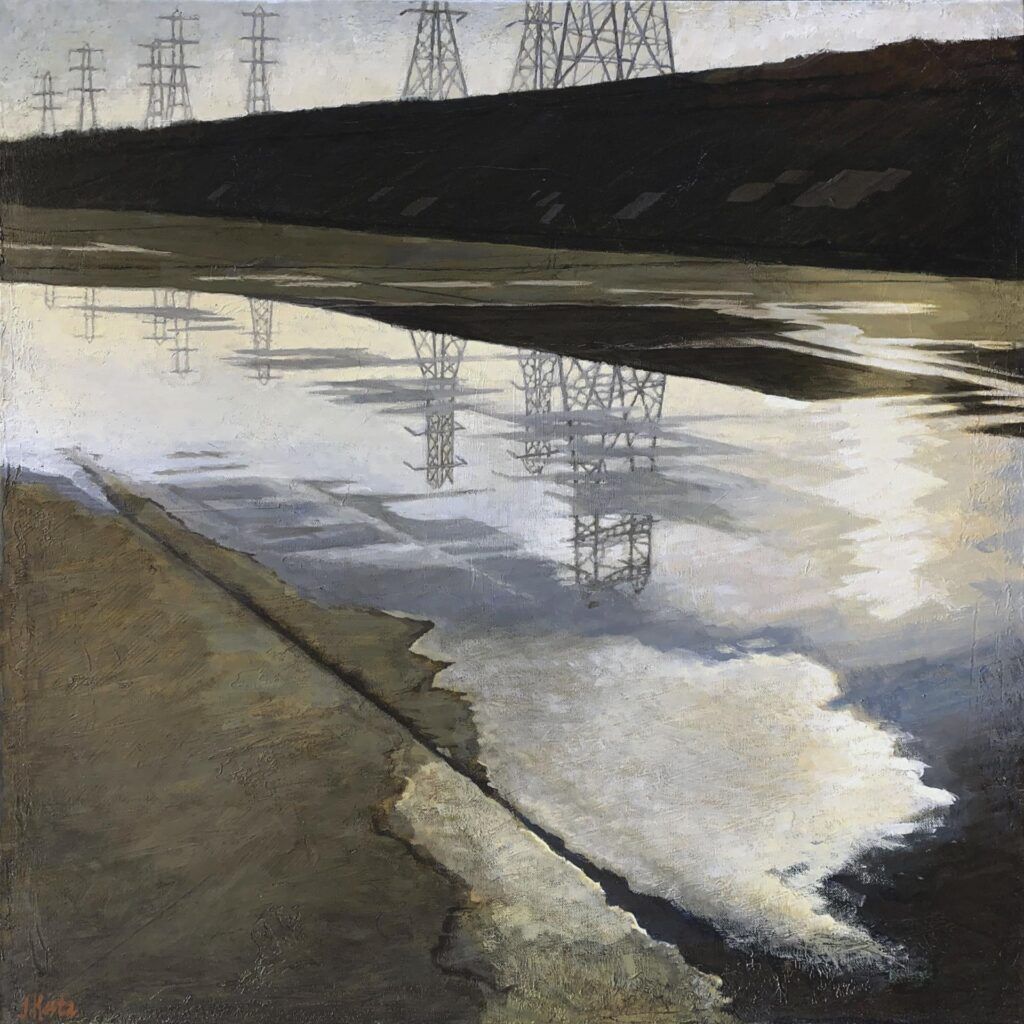

John Kosta's Los Angeles River series

Sotto Street Bridge and Nature Reclaiming are two of the nearly 100 fine art paintings from Kosta's Los Angeles River Series project. To Learn more about Kosta's journey documenting the changes taking place with the Los Angeles River visit the Los Angeles River Series.

Los Angeles River #33 (Sotto St. Bridge)

Los Angeles River Series #14 -

Nature Reclaiming

More on the Los Angeles Revitalization Project

The official website for this tremendous undertaking by the City of Los Angeles.

An interactive map that highlights a number of the developments planned and occurring along the Los Angeles River.

Home of the Los Angles River Project, an organization dedicated to restoring the vital ecosystem along the river.